Approaching the Finish Line: Dr. Soman Abraham’s Lifelong Quest for a UTI Remedy

Soman Abraham, BS, MS, PhD, has been searching for an effective treatment for urinary tract infections (UTIs) for over 40 years. His recent discovery of a unique bladder immune response focused on repair rather than eradicating bacteria is guiding his efforts to create an effective vaccine.

UTIs are one of the most common bacterial infections. They’re unique and bewildering because they tend to recur even after successful treatment, which for some patients presents a lifelong struggle. Large numbers of recurrent UTI patients – a majority of whom are women – also suffer from anxiety and depression, factors that compound the disease. The chronic pain, together with frequent voiding and associated lack of sleep, can be both physically and mentally debilitating.

In many cases, a UTI recurs within six months of the first infection. Current vaccine strategies that include intramuscular injections to combat UTIs have had limited effects in reducing these recurrences.

The Quest Begins

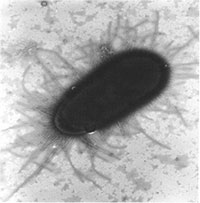

“When I began my PhD work in England in 1981, I sought to understand what was happening,” recalled Abraham. “We asked and answered several key questions over the years: Why is Escherichia coli (E. coli) the most common bacterial cause of bladder infections? What attributes of E. coli make it so pathogenic in the bladder?” Abraham found that E. coli bacteria are especially successful in infecting the bladder because they have the unique capacity to bind avidly to the bladder surface and resist the flushing action of urine. E. coli uses hair-like structures known as fimbriae to accomplish this, with an adhesive protein called FimH located at the tips of each fimbrial filament. (Figure 1). “This gives them the power to attach tightly to the bladder walls and resist the flushing action of urine. As fresh urine enters the bladder, adherent bacteria multiply in this medium, and within 20 minutes they can double in number, rapidly reaching numbers sufficient to initiate an infection,” said Abraham.

UTIs most commonly affect women, many of whom are young, healthy, and have strong immune systems. A question researchers struggled with was why these relatively healthy women experienced recurring UTIs when it would be expected that they would develop immunity against future infections after the first occurrence.

“The fact that healthy women kept coming back with UTIs again and again suggested some anomaly in the bladder immune system,” said Abraham.

Developing a UTI Vaccine

In spite of the questions regarding the immune system of the urinary tract, over the past three decades various researchers have attempted to develop a UTI vaccine. Many of the initial attempts have utilized a mixture of heat-killed uropathogenic bacteria as their vaccine. Abraham and few other researchers attempted a more refined approach. They theorized that a vaccine containing FimH protein might evoke antibodies that would block E.coli from binding to the bladder surface. In other words, they would prevent E.coli FimH from finding a binding partner on bladder cells. It was a similar idea to the one behind how the COVID-19 vaccine works.

In a study using mice, Abraham’s team found that vaccinating them with FimH protein evoked a strong antibody response in the circulation that offered 70% protection. This finding was in line with what other research labs had observed. However, when companies conducted human trials to test either the FimH vaccine or the vaccine comprising mixtures of uropathogenic bacteria in humans, they found that the antibody responses were weak and ineffective.

“This was very discouraging news,” recalled Abraham. “Then, we thought we’d take a different tactic – revisit what’s happening in the immune system in the bladder when UTIs occur. That’s when, after decades of searching, we finally found an answer!”

The Unique Bladder Immune Responses to Infections

To better understand the immune responses in the bladder, Abraham and his team started inducing multiple infections in their laboratory mice to mimic recurrent UTIs. They noticed a unique bladder immune response involving T cells that had been previously overlooked. Typically, there are two types of T lymphocytes recruited into infection sites: Th1 cells, which kill off pathogens as well as cells harboring pathogens, and Th2 cells, that arrive to repair tissue damaged by infection. Normally when an infection occurs, they both target the infected area. However, with UTIs, the majority arriving to the bladder were Th2 cells, which Abraham found surprising.

“It seems as though the Th2 cells involved in repair are rapidly mobilized to the bladder in large numbers, almost at the expense of the Th1, the cells that kill off bacteria,” Abraham observed. “As a result of the inadequate recruitment of Th1 cells, infectious E.coli in the bladder were not completely cleared. In fact, pockets of residual bacteria were found to be hiding within the epithelial lining of the bladder.”

In their intracellular location, bacteria were unresponsive to antibiotics and could persist in a quiescent phase for months before re-emerging to initiate another UTI. The intracellular location of these bladder bacteria could also explain why vaccines evoking antibodies to FimH or to uropathogenic bacteria were never able to completely eliminate bladder bacteria.

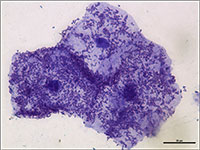

The bladder is lined with unique epithelial cells that are tightly bound to one another. The surface of these cells is coated with a specialized structure resembling chain mail, composed of proteins known as uroplakins. Together, they form an impermeable barrier against urine. (Figure 2)

Abraham’s studies in mice found that when uropathogenic E. coli enter the bladder, they quickly multiply in urine and attach in large numbers to the bladder surface, some even entering the cells lining the bladder (Figure 3). In response to this invasion, the outermost layer of the epithelium undergoes widespread shedding, an action not observed in other body sites. While this remarkable response reduces the bacterial load in the bladder by up to 90% (Figure 4), it nonetheless exposes the underlying tissue to toxic components in the urine. Indeed, some of the burning sensation experienced during acute UTIs is due to salts and other harmful substances in urine coming into contact with the underlying bladder tissue.

Given the severe pathological consequences of losing the superficial bladder lining, it is not surprising that the bladder is preoccupied in repairing itself by selectively recruiting Th2 cells at the expense of Th1 cells. As a result of this disproportionate response, bladder bacteria are never completely eliminated (Figure 5), allowing them to persist to trigger another flare-up.

“With each UTI episode, the number of Th2 cells and the speed at which they arrive in the bladder increase, making the bladder more efficient at repairing itself and the lining increases in thickness,” said Abraham. “It’s like building muscle that becomes stronger and more responsive with repeated exercise. While the Th2 cell response grows more powerful with each infection, the Th1 response correspondingly weakens, predisposing the multi-infected bladder to recurrent infections.”

The Science Behind a New UTI Vaccine

These discoveries revealed a key and long overlooked role played by T cells in combatting UTIs. They also pointed to a novel target for vaccine development. In the wake of this new understanding, Abraham began forming the idea for a distinct and more efficacious UTI vaccine. He hypothesized that if one could preemptively recruit Th1 cells capable of attacking FimH-expressing E.coli into the bladder, it would not only protect the bladder from E.coli infections but also prevent the persistence of any residual bacteria. Thus, even if the bladder preferentially focused on repairing its lining during UTIs by recruiting Th2 cells, there would be sufficient numbers of Th1 already present to keep E. coli infection at bay.

Abraham and his team theorized that a vaccine formulation comprising of an adjuvant (an immune boosting agent) that selectively recruits Th1 cells combined with FimH protein could promote bacterial clearance. Since it is critical that this Th1 immune response be directed to the bladder, it would be necessary that the vaccine be delivered there. It was also expected that this vaccination strategy would induce production of circulating FimH-specific antibodies which contribute to protection, although not against intracellular bacteria.

Indeed, the Abraham team found that instilling this new vaccine formulation in the bladders of mice not only evoked a strong circulating antibody response to FimH but also, importantly, a strong Th1 response in the bladder. When these immunized mice were challenged with E.coli-induced UTIs, the mice were protected from infection. It also completely eliminated residual bacteria that normally persist in the bladder post-infection, even in mice that have experienced multiple UTIs. So, giving the vaccine formulation directly into the bladder was the key to bringing in Th1 cells that normally wouldn’t arrive to clear all the hidden bacteria.

Significant Advances

Adapting the vaccine for human use presents several additional challenges. Abraham’s team has recently overcome one key hurdle. While injecting small volumes of their novel UTI vaccine into the mouse bladder space using a catheter evoked a strong protective immune response, this approach is not feasible in human bladders, which are many times larger. Conceivably, large volumes of the vaccine (e.g. 20 mls) would be needed to have its intended effect, which is neither practical nor affordable. The relatively large volume of vaccine is required because only a small portion of the vaccine is absorbed by the bladder lining due to its impregnable nature. So, in order to deliver adequate amounts of vaccine, frequent booster doses would be required.

“Clearly this limitation represented a significant hurdle,” said Abraham. “Recently, we found that we could overcome this hurdle by injecting small volumes of the vaccine into the bladder cavity along with an agent that temporarily breaks down the bladder barrier. Making the bladder wall leaky at sites of vaccine deposition allows for easy penetrance of all of the vaccine into the tissue.”

In April 2023, Abraham and Professor of Pathology Herman Staats, PhD, were awarded a two-year R21 grant titled “A Novel Vaccination Strategy to Curb recUTIs” from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The grant enabled Abraham's team to examine whether they could enhance their vaccine regimen by reducing the number of booster doses needed. This involved modifying the components of the vaccine and identifying additional clinical indicators of its effectiveness. The new information should facilitate the approval process from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical studies.

“I believe there is renewed enthusiasm for vaccines, especially following the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Abraham.

Other Milestones to Meet

The R21 study is aimed at optimizing the delivery of the UTI vaccine in the bladder cavity and identifying potential markers of vaccine efficacy that can be utilized during human clinical trials. Another milestone that will facilitate early approval of a clinical study by the FDA is demonstrating the efficacy of the vaccine in a second animal species.

Abraham’s lab plans to test the efficacy of their UTI vaccine in preventing E.coli-induced bladder infections in rabbits. The rabbit bladder has many similarities to that of humans and therefore should provide valuable insights to how human bladders are likely to respond to the UTI vaccine.

A major step is securing funding for the clinical study. Abraham is pursuing two sources simultaneously. The first is the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the second is from industry or public-private partnerships, which is being sought with the help of Dennis Thomas, PhD, associate director of Duke's Office for Translation & Commercialization.

Approaching the Finish Line

A UTI vaccine can’t come soon enough. The adverse psychological effects of UTIs can be as debilitating as the physical pain of infection.

“I regularly receive emails and phone calls from UTI patients or their relatives inquiring about the vaccine and being part of the trial,” said Abraham. “One caller even inquired about its use for their cat’s UTI!

UTIs, like many conditions that predominantly affect women, have long been under-studied.

“In light of the fact that there are more women in positions of power at the NIH and other research funding agencies now, there is hope that this perception will change. Indeed, officials at the NIH have recently indicated that they are especially interested in a vaccine against UTIs and that it is one of their top priorities.

Abraham has also developed a potential new approach to treating UTI symptoms. On March 1, 2024, he published a paper with his colleagues in the journal Science Immunology that identified the likely cause of persistent pain in people with recurring UTIs, even after a round of antibiotics. The paper outlined the crosstalk between mast cells and nerves which causes chronic pain and frequent voiding, which are common symptoms for those suffering repeat UTIs. It provided a possible new approach to managing symptoms.

“I feel a sense of satisfaction of coming to a point where we actually imagine a future for all this work we’ve put in,” mused Abraham. “You can see the promised land, the fruits of our labor. We haven’t reached it yet, but we can see it in the distant horizon. All these years we were working, we had no way of knowing whether we were on the right track or not. For the first time I have a feeling that maybe something will finally work out. There will be unforeseen challenges, of course, but I feel like we are closer than ever before to making a meaningful contribution for everyday people.”

For further reading:

- An Overgrowth of Nerve Cells Appears to Cause Lingering Symptoms After Recurrent UTIs (DukeHealth News, Feb. 21, 2024)

- Direct Bladder Vaccination Halts Recurrent UTIs” (BioWorld, March 12, 2021)

- “Abraham Featured in TV Interview About UTI Vaccine” (www.pathology.edu, May 19, 2021)

- Developing a UTI Vaccine That Expands Beyond Uro-vaxom and Uromune: Interview with Dr. Soman Abraham (www.liveutifree.com, Aug. 8, 2024)

- Live UTI Free is an international community of researchers, clinicians, patients and women’s health advocates based in Europe.