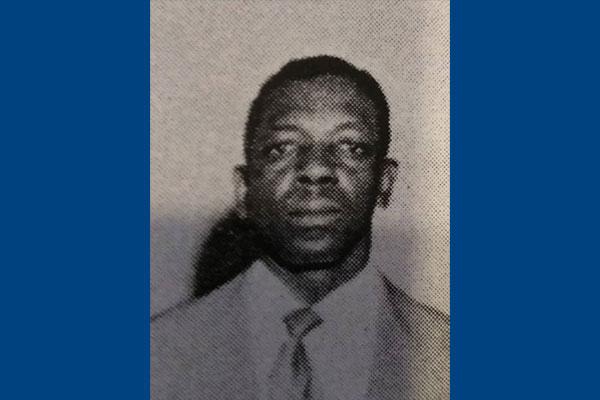

Before Donald Nelson Love (1907-1985) arrived at Duke Hospital on the morning of June 2, 1930, to begin his first day of work, he had never seen the place before. The hospital and medical school were still under construction, a month away from opening. Love wasn’t even sure he was in the right building.

Eventually, though, a friendly man approached and introduced himself: Wilburt C. Davison, MD, the founding dean of the Duke University School of Medicine. As Davison showed Love around the hospital and school, making their way around piles of construction materials, Love marveled at “this giant of a building.” Eventually, he came to know every inch of it: he remained on the staff for the next 44 years. He spent the majority of his career with the Department of Pathology, which he joined about 15 years after starting at the hospital.

Love was, if not the first Black employee at Duke Hospital and the School of Medicine, one of the first, joining the organization during a time of enforced segregation. Love had a passionate interest in civil rights and actively advocated on behalf of himself and others who were marginalized as a result of segregation.

He wrote that he “had come to the Hospital for a job that I got through my father, John Love, who operated a printing machine on the East Campus for many years.” His father had become acquainted with Davison, and the dean hired the younger Love to join the team in a support role with responsibilities that included readying wards for use, changing linens, and various other housekeeping items.

William Webb Johnston, MD’59, started the Division of Cytology within the Department of Pathology and served as the Chief of Cytopathology for 25 years until his retirement. He remembers Love well.

He observed that the School of Medicine opened in a Durham that was, at the time, “a little country town,” and noted that Wiley Davis Forbus, MD, a pathologist and medical educator with a degree from Johns Hopkins University, was instrumental in forming the faculty, staff, and program of the newly established school in 1930.

To staff the school and hospital, Forbus reached out to find local people who could fill specialized roles, noted Johnston. Forbus brought them in and trained them, because at the time there was nobody on staff trained to this work.

“Everybody worked hard and together,” recalled Love. “Everybody knew everybody. It was a united effort on a united front. There was a lot to do in a short time and not much help to do it.”

That spirit of unity and collective purpose was undermined by racist segregated policies of the time to which people of color were routinely subjected. Love’s youngest daughter, Pearlie Love Lewis, recalled that one of her father’s tasks was to guide hospital visitors by pressing the elevator button. Then, he had to run up the stairs to meet them, because Black people weren’t allowed in the same elevators at the time.

Despite such challenges, Love’s role in the organization grew as he acquired new experiences and skills. Once he joined the Department of Pathology, Love served as an assistant for the Department of Pathology’s autopsy service and was responsible for preparing gross specimens for teaching — organs used to teach medical students anatomy. Johnston recalls the department halls lined with white cots holding hundreds of specimens that Love helped prepare.

“I remember Donald Love very well, with a great deal of affection and respect,” Johnston recalled. “He was a very integral member of the department. Former department chair Forbus depended on him for a lot of services.”

Love’s skills included transferring specimens into special preservative solutions to be presented at autopsy conferences.

“He knew a tremendous amount of pathology, and would comment about the organs and our performance of the autopsy,” remembered Johnston. “He was rather astute and learned on the job.”

Donald Love Service Award Reinstated

In 1993 George Margolis, MD, with the support of Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans, chair of the Board of Trustees of the Duke Endowment, presented the idea of honoring Love with the creation of Pathology Department Service Awards, consisting of a Lifetime Service Award and a Self-Development Award. The initial idea was that the annual award would be given to an employee in Duke’s surgical pathology laboratories who had who had advanced their abilities and skills to make important contributions to the department, as exemplified by Donald Love.

The recipient of the Lifetime Service Award was identified as one “whose work ethic and efforts [were] most exemplary and/or who [had] been acknowledged by peers and staff as best serving Anatomical Pathology’s mission.” The Self-Development Award was originally distinguished “by a career of self-development through educational endeavors which [had] substantially changed the course of his or her life or career.”

In the original award announcement in 1993, Love was recognized as a man of high accomplishments and perseverance who “served humanity with altruistic compassion. The extra mile always seemed to be the easiest for him to travel.”

When the award was established, then-Chancellor for Health Affairs Ralph Snyderman, MD, called it important and overdue.

“Though there has been improvement in equality over the years, the job is far from finished,” said Snyderman, who was chancellor from 1989 to 2004. “This tribute to Donald Love is the first in a long series of steps to create an environment where the talents and contributions of all our employees are valued.”

Awards were given to 11 recipients between 1993 and 1997, and the department reestablished it in February 2022 by awarding it to Staff Assistant Ebony Ambrose, and in 2023 to Program Coordinator Brittany Harris. The awards provide financial support in the form of reimbursement to staff members enrolled in certificate or degree programs, to assist with incidental costs associated with pursuit of these programs.

In a 1993 memo addressed to Leonard Beckum, vice president and vice provost of Duke University at the time, Margolis wrote, “Out of my career-long immersion in medical education, I consider my participation in the creation of this fund as my most fulfilling experience. His story has been cited as an extraordinary part of Duke’s history. This award is a prize to match his vision: to further the education of medical students, memorialized by the creation of more than a token prize in his name. Absent this memorial, a Black employee, whose ties to Duke Hospital and Medical School began with the opening of the institution and spanned more than four decades, would have disappeared from history.”

Margolis’ son Joshua later wrote about his father’s friendship with Love in a paper titled “Dinner with Donald” for Duke’s “Humanitarian Perspectives in Public Policy” course in 1981.

“I have a warm memory of Donald,” said Johnston. “He was always there, always doing his work. Everybody had tremendous amount of respect and affection for him. I think it’s wonderful that we’re reinstating the service award.” .

Love’s Daughter Follows in His Footsteps

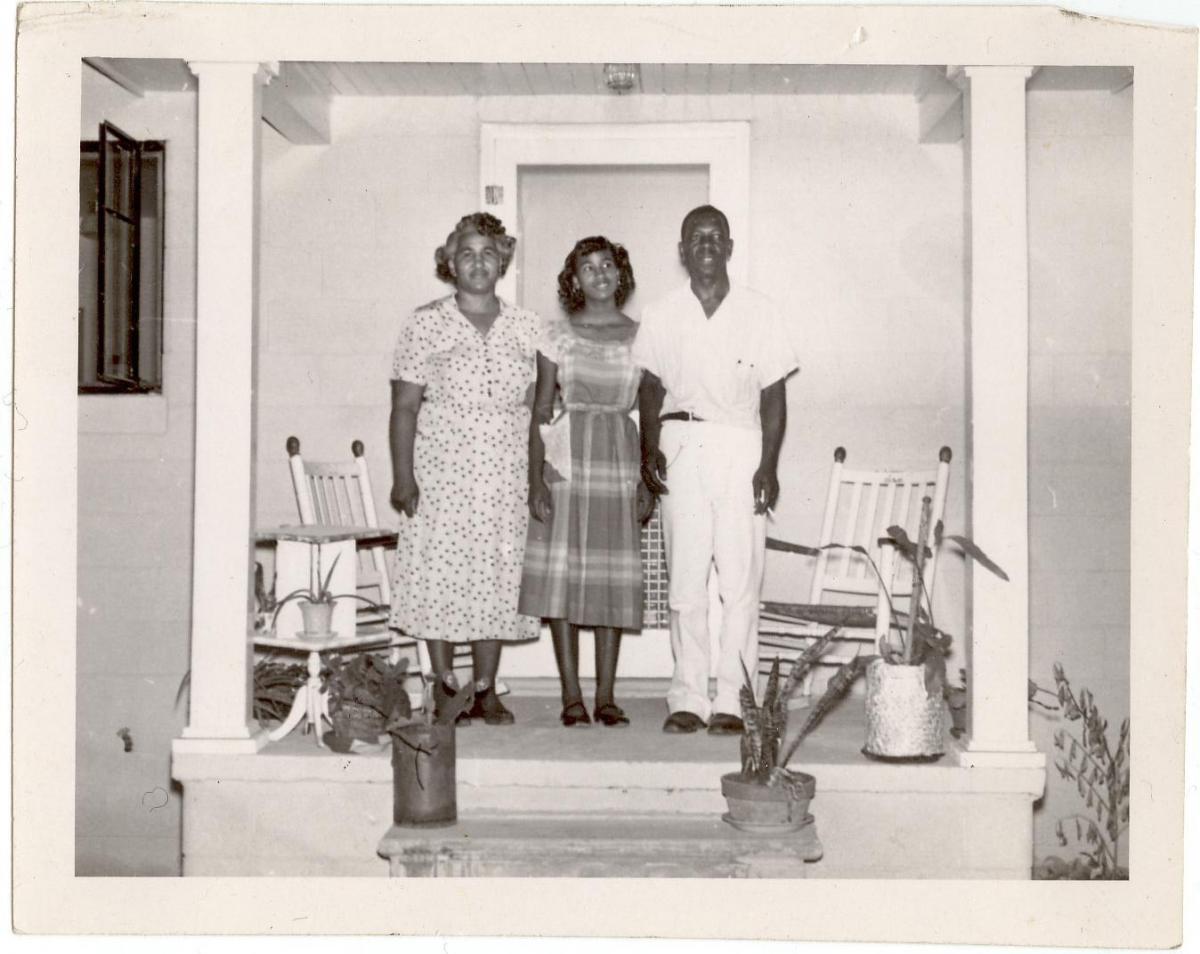

Donald Love’s surviving daughter, Pearlie Love Lewis, lives in Durham and retired in 2004 from IBM, where she was a systems analyst. Her husband is Guster Lewis, Jr., and they have a daughter, Deidra Lewis, who is a global business services operations manager with United Parcel Service in Durham. Their grandson, Ronald Christian Lee, is employed by Durham Public Schools.

“My dad was the youngest of five children,” said Lewis. “He and I were very close and I learned a lot from him, like how to stay focused and try to always do good by other people. We came from a very religious family. We believed in doing everything we could for others, being good to everybody. My father did that through teaching Sunday school, hosting speaking engagements, and serving as president of PTA for my elementary school. He also wrote religious weekly articles for the Carolina Times Newspaper for over 10 years.”

As a young girl, Lewis used to run and skip up and down the Duke Pathology Department halls. She remembers when she came to the hospital to have her tonsils removed. When she realized they were going to give her a shot, she snuck out and says she “escaped to the Pathology halls to hide.”

“My father had a garden and invited Pathology Department members and their families to come out and tend the garden and plant together,” Lewis remembers.

“My family offers special thanks to the Semans and Margolis families for making this dream a reality,” said Lewis about the Service Award. “We vow to embrace the award winner into our family, just as my father would have.”